The Known Unknowns #11: Endings, Revisited; or: Get Behind Me, Satan!

The Known Unknowns is a weekly series of posts about the things that bedevil me in my writing life. It’s a catalog of what I’ve learned, and am still learning, from years of missteps, blind lunges, and thick-headed perseverance.

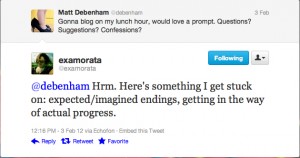

You’ve surely seen my other regular feature on this blog, called Ask A Seasoned Semi-Pro, my advice column for writers. As it’s a prompted piece, I generally put out the call on Twitter for questions and ideas. For the most recent installment, I received several, two of which I used. The one above, though, struck something else in me. What that was, I wasn’t sure at the time, and that’s how I knew it was a Known Unknown.

If this column* is about one thing, it’s about progress: What hampers you, what suddenly vaults you beyond where you ever thought you’d be. And I’ve talked quite a bit before about finishing things. But then there’s the actual ending to the thing you’re writing. And how awful would it be if that ending were the thing that was keeping you from progressing?

A lot of people don’t know how to end a story. Either they’re not sure how an ending is supposed to go, or they can’t seem to find one, and they just go and go — like Grady Tripp in Michael Chabon’s novel Wonder Boys, or Spalding Grey in his monologue Monster In A Box. Then there’s what @examorata describes, which is the horror of having an ending in mind and not being able to meet it. And then the more you write, the further away from shore you seem to be getting. This can be an incredible source of anxiety, even irritation. We get angry with ourselves for not being able to just finish the damn thing, as though knowing where a thing ends is the same as knowing how to write an ending.

I just used a swimming/shore/drowning image to describe this, but it occurs to me it’s more like renovating a floor. I’ve done a few floors with a few different materials, and there’s nothing quite like the terror of being halfway through a beautiful-looking job and realizing This. Is. Not. Going. To. Be. Right. What looked great now promises to be terribly wrong, like a false eyelash hanging askew in a rainstorm. Except people are expected to walk on this thing and live on top of it and to not think every day: What the fuck happened here?

The fact is, having an ending in mind can be great. Amy Hempel has said she always knows the last line of a story. It’s an old saw that mystery writers start at the ending and plot backwards. That’s a lot different, though, from having an ending to your story in mind and keeping your eyes locked on that, no matter what the actual writing of that story is telling you.

I was in my second semester of grad school when a teacher told me, “You need to relax when you’re writing.” I told her I had no idea what this meant. I thought: What, candles? A little whiskey? “I can see you plotting,” she explained. “You have an idea for how these are going to go, and you write toward that, and it will never feel anything but forced. Relax. Get inside the characters a little more.” This lit the panic-fuse in me. This was a teacher I’d wanted very much to impress. I was sure I was the future of the short story, and for her to not like something I did was an unacceptable outcome. I worked at stories all semester long — six submission packets, 40 pages each of highly plotted, surely ingenious stories — yet I never seemed to hit the mark. My teacher’s responses to my work became more exasperated, and more terse. “I’m not sure what you’re trying to do here,” went one. This was a specific comment about a scene in a story, but it could just as easily have applied to my entire existence in the MFA program. It was here that I honestly questioned my decision to go to graduate school at 32, not to mention whether I should even be writing.

By the last submission, I’d grown so frustrated with myself and with my teacher’s Jedi bullshit that I said “fuck it” to trying to please her and wrote something that was weird and fun. And I was sure she’d hate it. The story was set in my parents’ home city of Pittsburgh, a place I’d visited and puzzled over every year of my childhood. It was about a lost young guy, newly arrived in cold, off-putting Pittsburgh, trying to reinvent himself as a theater actor. (He was a trade-school kid.) He meets a slightly older woman who dresses and speaks in a manner befitting the 1950s, not the 2000s. They flirt and end up on a nice date. The next day, at her invitation, he takes the bus to her house. There he discovers her entire family’s living in this 1950s style, seemingly unaware of the modern world. What had first seemed charming and quirky is now dark and upsetting. He’s decided to bolt, but then learns the reason why the family is living this way. In the end, he decides to stay, living their way while slowly upgrading their dangerous wiring and fixing all the things that have fallen into disrepair.

Now: looking at the story now — and I just did, for the first time in nearly a decade — I’m under no illusion that this story is great or even good. And when I look at my teacher’s response to it, I notice now that she never really praises the story, but instead is rapturous in her praise of my writing the story. “YES!” she wrote. “THIS IS WHAT I’M TALKING ABOUT.” In fact, her one negative comment about the whole thing was regarding the title — I called it “Pgh” — which she rightly found weird and cryptic. (Pgh is how people from Pittsburgh shorthand the name of their city. Or how they used to, anyway.)

Well, now I was really confused. And for most of the next semester, I still didn’t quite get it. Where had I gone right? When I look at the story now, I see a quirkfest that would bug the fuck out of me if I read it in a magazine. But I also see a story that, for all the self-consciousness of its situations, has some good stuff going for it. The characters have a nice rapport, there’s very little exposition in the dialogue, there are some interesting observations. Moreover, the story’s weirdly sad and uplifting at the same time, and there’s some real humor in it. When I read my teacher’s letter to me now, these are the things she responded to, and these of course are the things that can go a long way toward making fiction into a livable habitat for readers. When she was telling me to relax and stop forcing things, she didn’t mean not to have situations and not to have plot developments. She meant not to let those things be EVERYTHING in a story, dummy. Stop trying to make magic happen, and start letting your characters be clueless and petty and bullheaded, because these things make for interesting people, and — if you let them — they will help make for an interesting story. Oh: And have some of yourself in it. When I wrote that “Pgh” story, I was writing about all the times I’d let myself get into uncomfortable situations because I didn’t know how to say, “Wait. This feels wrong.” And I was writing about the weird, stuck-in-time place Pittsburgh was all the times I’d been there. (It’s a good deal better now.) And I was writing about how you meet someone who may be The One and then you realize you will be asked to take on their whole family and all the complications that come with that. Was I aware from the start that I was putting these things, these feelings and experiences, into the story? No. I was too busy having fun, seeing where it went. And I never thought once about where it would end. And this is where I went right for the first time.

When you write something for others to enjoy, you have to perform a devious trick: You have to give them an authentic experience which is 100% manufactured by you via the manipulation of words yet which must also mean more to you than your reader may ever know. In other words, you could write very directly about what it feels like to wonder if you’re too much of a bully on your child’s behalf. And someone may read that and say, “Sure, I feel that way sometimes, too! Thanks for pointing that out!” That’s a specific, direct reaction to a specific, direct piece of writing.

But if you take those same awful, complicated, shame-filled feelings and refract them through the prism of a dramatic situation, suddenly they may feel more universal. If you’re lucky, you may tap into something a LOT of people feel about parenting, or childhood, whether or not they can actually relate to the specifics of the dramatic situation. The situation is fake, the feelings are real, and the words are arranged in such a way to make these things line up like the lenses in a telescope. (Figurative language ahoy today!) Yet when you’re writing the thing, you also have to convince yourself that there’s no way possible you’re being manipulative. You have to swallow the feelings, immerse yourself in the dramatic situation, and pray the feelings magically ooze out through your fingertips and somehow get into the computer, like a reverse Videodrome.

If you keep a fix on the ending — always one eye on the clock, as it were — you may miss ALL of this. There’s a psychological disorder in certain kids (and, uh, grownups) called Oppositional Defiant Disorder. A child with this is so inflexible — so unable to even process Possibility — that when presented with a change in plans or an altered schedule, they become angry and violent. (This is also called The Explosive Child phenomenon.) I feel like this is what happens when we notice that our story is not going where we thought it was supposed to go. Instead of thinking, “Okay, this is interesting. Let’s see what the new plan is,” we panic and shut down and go “NOOOOOOO!!”

I have a lot of bad writing habits — a LOT — and I’m forever throwing things away and restarting them because I realize too late that I’m DOING THAT GODDAMN THING AGAIN. But one habit I’ve long been cured of is the habit of holding on to an ending. If I show a draft to someone and they say, “Yeah, that ending doesn’t work for me,” my response is: “Good to know! I’ll see what I can do.” Look at it this way: No one’s ever recommended a book or story or movie to you and said, “The whole story sucks, but the ending is GENIUS.” So stop looking at your “ending” as THE ending, because it can’t be that unless everything else in your story says it is. It’s not that endings aren’t important — watch a Saturday Night Live sketch sometime and tell me they’re not — it’s that if you have good characters and you’re willing to get them into fascinating situations while remaining aware of who these people are, the right ending is there, waiting for you. It just may not be where you thought you put it.

* Please know that while I’m writing these, I am wearing a grey fedora with a PRESS card tucked in the band.

Main “END” photo by Naomi Ibuki. Used under Creative Commons, via Compfight.com

Thank you!! That actually reminded me of some student-teacher interactions I had long ago, and wondering where I lost what she had reacted to.

Awesome!

Also, gah, reverse Videodrome.