Your Lead Character is a Nutjob – if You’re Doing it Right

Journalist Oliver Willis, writing recently in the Daily Banter, says that conspiracy theories are “the mind’s way of dealing with a world that seems to be turned on its ear.” If you use social media even casually, you’ve had a front-row seat to the flourishing of this condition over the last few years. The twice-daily Lucky Slots invitations from Aunt Pat are one thing, but why is she posting about False Flags and the various Socialist agendas of our President? Was she always like this, or has the semi-anonymity of Facebook freed something dark and weird from within her?

As a creative type, you can choose to be disturbed by all this, or you can choose to exploit it for the betterment of your work. (And yes, those are almost always your available choices.) Willis’ quote is saying people develop extraordinary beliefs in order to compensate for a world that makes increasingly little sense to them. But look even closer:

It’s not that the world itself doesn’t make sense. It’s that it has ceased to look right within the fragile narrative framework generated by the person viewing it.

Guys, this is fiction gold.

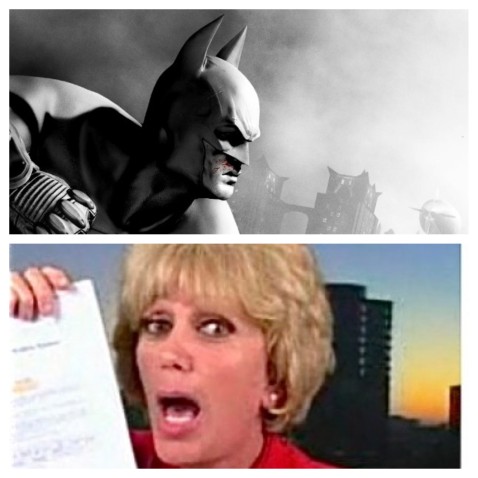

We’re each, as someone once said, the hero of our own story. But as Batman and Don Quixote both remind us, you have to be fairly screwed up to consider yourself a hero. Add to that the fact that everything is wildly beyond our control, and you have what it takes to create good fictional characters.

I’ve said before that characters need to be driven and damaged. In real life, you’re a reasonable person, right? If the light turns red, you stop. If someone says, “Don’t go in there!” you don’t go barging through the door. And since you’ve never been near a bull, you know not to drop everything and pursue your dream of becoming a bullfighter. Good fictional characters do not know this. They don’t stop at red, and the person telling them not to go in there is, in that moment, yet another mortal enemy in a long series of mortal enemies. Good fictional characters are nutjobs.

In other words, like Aunt Pat, your characters have a narrative of their own, one they believe to be true, one they cling to like a rope. One which, were it severed, would cause them to spiral into oblivion. They’re deranged*, in the best possible ways.

Driven and damaged is pretty non-negotiable. Because the demands of living in a fictional narrative are unrealistic and extreme, so must be the sense of self required to function in that narrative. An ordinary person would walk away, or settle. If your fictional character does that, the story ends too early. This doesn’t mean your character is an asshole 24/7, and it doesn’t mean you need to put them in extreme situations all the time. Just “slightly unbelievable” will do.

Most orphans in Victorian England did the best they could, growing up in orphanages and living whatever lives were handed to them, if they managed to make it to adulthood. You do not want to read that book, at least not more than once. You DO want to read Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, because those two monkeys are of a slightly heightened reality, are they not? They’re made not only of sterner stuff, but of weirder stuff. They’re not right in the head, is what I’m saying, and we reap the rewards.

The female characters in The Scarlet Letter and Little Women occupy the same state as each other, both geographically and psychologically. They live in Massachusetts, about a half hour’s drive (car-wise, anyway) down Route 2 from each other, and while they take very different courses in their lives, they’re all just a little more independent and (ugh) “strong-willed” than was permissible or advisable in the eras of their creation. But if they weren’t, there’d be no story for any of them. What’s that bumper sticker? “Well-behaved women seldom make history”? (Note: This is a quote from Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, writing about — ta-da! — Puritan funeral services.) Well, “well-behaved” women never make good fiction.

All this comes down to is understanding what it means to make an “active” character. We’re told all the time characters need to be active, and so you see a lot of student fiction where people smoke and half-talk and then suddenly they’re robbing a liquor store, as though the writer had just remembered, Damn, I forgot to make him active! And while robbing a store (in my pissy straw man example) is certainly an act, what about that character ever felt like this was something they might do? I mean, come on: You read that stuff and if the prose is good, you might feel something like excitement, but what then? You feel cheap and cheated. Welcome to the post-fiction refractory period.

In my twenties, I used to never shut up about the importance of “incident,” by the way, and I could show you a dozen stories where incident is piled on like the possessions in the back of the Beverly Hillbillies’ pickup. Then someone in a writers’ group would say, “Yeah, but this doesn’t feel earned,” and I’d silently pity them.

This is why thinking of characters as “driven and damaged” helps me more than “active.” Active is pretty vague. It’s like telling someone to be healthier. Thanks! I’ll get right on that! Give them specifics, though — hey, try yoga and walking and maybe don’t eat four Trader Joe’s mixed-berry turnovers in an eight-minute span** — and then you’re actually being helpful.

Likewise, driven and damaged does not preclude seemingly passive characters. Look at guys like Lewis Miner in Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land, or Jeff Lebowski in the movie The Big Lebowski: Two slackers who nonetheless work exhaustingly hard to retain their hold on slackerdom. The world around each of them is demanding something, and they resist to a degree which is unrealistic, possibly pathological. But because of that, they are good fictional characters. Also because of that — the world around them demands one thing, they demand another — you have tension, which creates stakes. They have things they care about, even if what they care about most is maintaining the cocoon of not caring about things.

Our job is to figure out both sides of the equation: What does Aunt Pat need the world to look like? And what is the world giving her instead? Then our job is to set some things in motion, playing these two sides against each other. Aunt Pat, tired of getting no “likes” for her angry Facebook comments, decides to do something about it. So she becomes a domestic terrorist. Or she forms a home school and offers it to the parents in her neighborhood. Or she starts a newsletter. Or she sets out for Africa to prove once and for all that Barack Obama is a Kenyan-born Muslim Socialist who may also be the literal Antichrist. And she makes it to Kenya. But then…

The “but then…” is your actual story. The first part, whichever route you choose for Aunt Pat, is just your premise. Aunt Pat has ideas. The world seems to contradict this, or to hold final confirmation of her ideas tantalizingly out of reach. That’s a buddy comedy right there, Aunt Pat and The World.

Look at the characters you like in any kind of fiction. Tell me they’re not at least mild nutjobs. Sam Malone, a recovering alcoholic, not only owns the bar he works in, he goes there every day believing this will be the day he’ll get Diane or Rebecca to love him. Despite the fact that he can’t stop sleeping around, and despite the fact that he has zero interest in true self-improvement. Driven and damaged is Sam Malone of Cheers.

Diane Chambers, for her part, is a highly intelligent academic who would seem to have the wherewithal to at least get a job working for a college, if not teaching at one. Or a bookstore, which, in 1980s Boston, was probably not a bad gig. Certainly better than showing up every night for tips at a fairly underpopulated bar where she knows she’ll endure sexual harassment and verbal abuse all night long. But Diane is driven to try and improve the lowlifes around her, while also being damaged enough to feel an abusive family is better than no family at all.

Let’s not even get too far into Cliff Huxtable, a capable obstetrician who nonetheless practices from home, clearly so he can keep an eye on his daughters and drive away their potential male suitors, while encouraging his lone son in his hapless pursuit of girls. Meanwhile, he employs sarcastic and cutting humor with all his children, rarely showing real affection toward them. Rather, he expects them to realize that when he eases up on them, that’s his love. And he maintains a mother-son relationship with his wife, Claire. Cliff Huxtable, in one of the harshest dramas ever televised, is driven to surround himself with a large family, but is too damaged to love them properly.

You can do this all day, believe me. And in this way, your main character certainly is a hero. A hero is, as we know, not the one who goes along to get along. A hero is, of course, The One Who… That’s how we’re able to recognize them. But do know that why they’re The One Who… is because there’s something deeply, wonderfully broken about them. They are deranged. They are nutjobs. They simply can’t accept their world for the way it is, so don’t let them. Instead, turn them loose on your pages.

* I want to be very careful here and explain that I do not mean the insane, i.e., people who are unable to function to one degree or another, who cannot distinguish right from wrong. Nutjobs are people who may otherwise be able to function, who can normally tell right from wrong, yet who lapse into a kind of situational insanity in order to deal with environmental pressures.

** Don’t really say this to me. Just keep out of it.

One Response to “Your Lead Character is a Nutjob – if You’re Doing it Right”