LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! How to Write a Chase Scene the MARATHON MAN Way

LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! is a series of pieces looking at what fiction writers can borrow, craftily, from other sources. I will mostly look at television, movies, and comics, though the occasional literary work may squeak its way in, as will a song or two. LET’S STEAL FROM THIS! finds useful inspiration in unlikely places.

Ever read Marathon Man? I’m sure you’ve seen the movie, but have you read the book? It’s pretty fantastic. It’s by William Goldman, who also wrote the screenplay, as well as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, and The Princess Bride, among others. Both movie and book are much, much more than the famous “Is it safe?” scene.

Marathon Man is about Babe Levy, a history PhD candidate at Columbia whose other passion is running. One night, when his older brother Doc turns up murdered, Babe is plunged into Doc’s secret life, one involving a government agency called The Division, hidden Nazis (Marathon Man takes place in the early ’70s), stolen diamonds, and Doc’s dangerous double-agent cohort, Janeway.

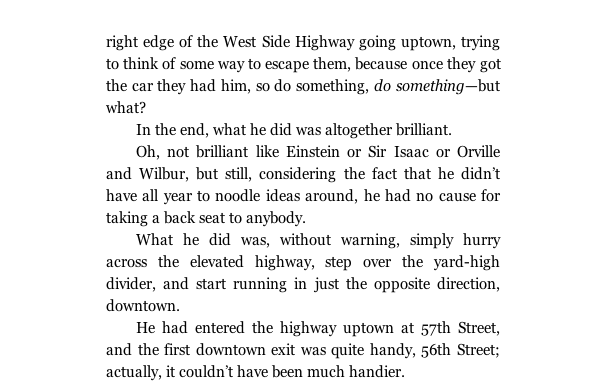

I have to thank my student Marshall Findlay for this, because he sent in chapter 24 of Marathon Man and said, “Can we talk about why this chase scene works so well?” I hadn’t seen the book in forever, though I read it twice in high school (thank you, Sunflower Book Exchange of Spencer, MA) and had actually rewatched the movie only a few months ago. When I looked at the chapter, several things stuck out. Here’s page one:

I’d remembered the book being mostly from Babe’s perspective, with occasional forays into his doomed brother Doc’s POV, but I was all wrong. In fact, chapter 24 opens in an omniscient voice and then settles into the head of Janeway for the first while.

This is not accidental. We need to feel like everything’s out of Babe’s control, and the best way to achieve that is by taking away his POV. When Janeway notices Babe limping off, we notice it. Then, only when Babe’s fully on the run are we back in his head — and very suddenly, with no line break, no space for adjustment, nothing.

Babe, after being tortured for information he never had to begin with, has decided to survive. This is good news, since he’s the hero of the story. But now Goldman has a problem on his hands: How do you show an extended, four-person chase scene in a book? I mean, he could avoid it entirely: Babe gets away, whoops! But then how menacing and dangerous does that make his captors? What would he have to fear for the rest of the book?

Goldman could also just write a chase scene, but have you ever read a chase scene in a book that you didn’t end up skimming just a little? It’s very hard to show sequential action in prose without things turning into appliance-setup instructions. He needs you in that scene, but the typical — he ran to the end of the street. He was out of breath now. Then he turned the corner and ran some more — isn’t gonna do it.

So Goldman does three things. One, in addition to the mangled tooth, he gives Babe a hurt foot — he’s a marathoner, we know, but he can’t be invincible here. (Also, Babe’s barefoot and in pajamas from having been taken from his apartment in the middle of the night.) Two, he makes Janeway a terrifyingly fast runner. And three, by putting long-distance-runner Babe in the first real race of his life (never mind for his life) he’s able to naturally introduce thoughts of Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian runner who stunned the world by winning the gold, barefoot, at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. This is who Babe would conjure up to keep himself going around the Central Park reservoir, and it’s what he does to keep going now — in a three-page single sentence detailing how Bikila beat the Russians at Tokyo*.

Now, consider this for a second. If you want to convey action, you blast out a bunch of short, simple sentences, right? That’s what we know from thriller writing, and it’s a thing even Graham Greene employs in The End of the Affair, when Sarah’s recounting her version of the fateful bombing scene. But Goldman’s thoroughly in Babe’s head — it’s close third-person — and just as he used Janeway’s POV to obscure Babe from us, he does the same here.

So for three pages we’ve now not only been in Babe’s head exclusively, we’ve also been caught up in the story of Bikila at the ’64 Olympics. And this does two things: one, it gives us a mini road-race narrative, a best possible scenario for Babe; and it also plays with the tension that grows in the reader’s mind as she gets pulled into the Bikila story while realizing: Wait, he’s running from guys with guns. Where are the guys with guns? And after three pages, finally, here comes the goon squad:

One short, simple sentence — And could he move — provides all the terror needed to snap us back into reality. Janeway is a real threat.

But again: there’s only so far traditional action writing can take you. So Goldman brings back Bikila — not in a memory, but as a kind of angel/coach for Babe.

Here, also, Goldman welcomes Paavo Nurmi to Babe’s coaching staff. Nurmi, a Finnish champion from the 1920s, is the other marathoner in Babe’s pantheon. And so he and Bikila guide Babe through his chase. But then Janeway lunges and brings Babe down!

So he rallies and gets up and then he’s off, unbeatable, because Janeway was his only real competition.

Except:

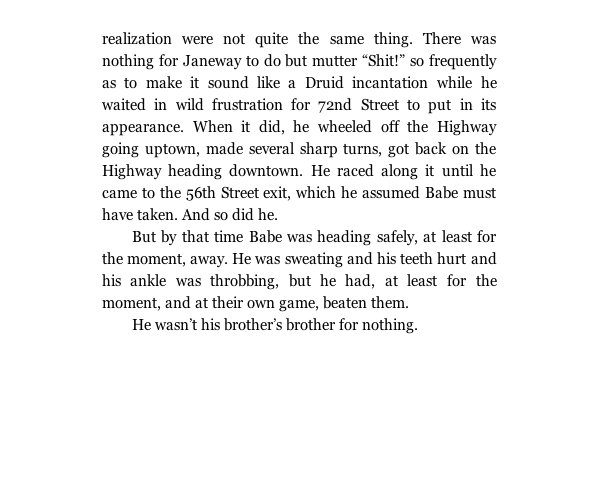

Now we have a whole other threat. You can outrun a pack of people, but you can’t outrun a vehicle. Furthermore, the incline he beat Janeway on was the on-ramp to the West Side Highway. No alleys or side-streets there, just miles of clean pavement for a car to casually spread you across. What’s he going to do?

Goldman plays this up by having Babe ask the questions we’re asking — first What the hell am I gonna do? and then do something — but what? Question-asking is a technique we all remember from storytelling time in nursery school — The wolf was coming, so what could the third pig do? — and it’s unbelievably effective in adult fiction. The first time I remember being fully aware of it as a technique was at a reading by the great Paul Lisicky. He was reading from his memoir, Famous Builder, and he used question-asking — in the piece, as his own narrator — to create tension and suspense in a scene about singing with a band in public for the first time. And it was goddamn magical.

So Babe, because he’s smarter than his hunters, does the simplest thing. He doesn’t jump off a building, he doesn’t crash through someone’s skylights, he doesn’t leap into the Hudson, which is maybe 30 feet away and could carry him to safety. He just steps over the divider.

Think about this. We’ve just been through a wringer of a torture scene with a Nazi, then this long chase with its reflective images of worldwide Olympic glory — and the resolution is the stepping-over of a highway barrier. This is the sign of an author in control, because when I read that I didn’t go, “Aww…” I went: “HA!” In surprise and admiration.

And Goldman knows this, so he also knows to get out while the getting’s good:

That’s the end of the scene, and the chapter. We’re not done here, not by a mile, because now that Babe’s seen his reflection in the river Styx, he comes back a changed man, a person who’s going to proceed differently than he did before his ordeal. (It’s no accident this section of the book is subtitled DEATH OF A MARATHON MAN.) And that means, if I may flip the cliche, the hunted has become the hunter. But that’s another chapter or five.

So what do we steal here? If we’re writing a chase scene or any suspense scene, do we have marathoners show up and talk to our hero? No, not directly. But look at what Goldman did: He distracted us with bickering, he surprised us with Babe’s initiative, he played with POV, he introduced real threats — Babe’s hurt tooth and foot; Janeway’s speed — and he used something from Babe’s own character — his love for these champion marathoners — to drive him on. In other words, he didn’t just write this scene, he played with it. He considered it. He threw everything he had at it.

By creating a dialogue between Bikila and Nurmi, he avoids a) straight author-driven narration; and b) Babe’s observations of the moment. Neither of these would be interesting, neither would create any kind of palpable churning in the reader’s gut. Instead, he immerses us in Babe’s total experience of the moment, everything from the physical to the mental to the metaphysical — to put us in his body, in that race.

You can certainly steal the ghost-marathoner technique wholesale, but remember that what makes it so effective is that here it arises naturally from Babe’s character. Again, this is what he thinks of when he’s trying to keep going on his morning run around Central Park, so it’d be what he thinks of when he’s running for his life. And because it’s true to who we know Babe to be, it avoids being a gimmick.

* I looked it up, and I’m sorry to say Bikila’s strongest competition at Tokyo were from England and Japan. But Goldman wrote this in the days before Wikipedia, and I’m glad he did it this way, with the Russians. Vastly more effective to use a team from another superpower than two guys from smaller countries.

AWESOME 1974 paperback book cover courtesy of Delacorte Press.