Known Unknowns #10: Woodshedding

The Known Unknowns is a weekly series of posts about the things that bedevil me in my writing life. It’s a catalog of what I’ve learned, and am still learning, from years of missteps, blind lunges, and thick-headed perseverance.

I first heard the term “woodshedding” when I was fourteen and a new drummer and thus a sweaty-handed reader of Modern Drummer magazine. I have no doubt older, established musicians read Modern Drummer with plenty of enthusiasm, but no one reads it with more excitement, fear, and wonder than a new drummer. (The only magazine I’ve ever loved equally in my life was probably Dragon. Shut up.)

In the very first issue I owned of Modern Drummer, the Art Blakey issue (September, 1984), at least two people — one possibly Blakey himself — used the term “woodshedding.” I had no idea what this could mean, but it was clearly a crucial word for a musician to know and use. Then I looked at the floor around my snare drum. It was littered with tiny blond splinters, wood shavings from hours of bashing my poorly controlled sticks against the rim of the snare. And I understood immediately: Woodshedding was just a cool word for “practicing.” Just like you’d shed some wood while whittling or sculpting something finer out of a branch or block, a musician would shed some metaphorical wood while getting better at his or her craft. Drummers were coolest because they would shed wood both metaphorical and literal. I felt smarter already!

By now you know the punchline: That’s not what’s meant at all by woodshedding! Woodshedding refers to the habit, among American jazz and blues musicians in the early twentieth century, of going out to the woodshed to practice in private. Now: I’ve suspected this meaning for a few years, but didn’t actually confirm it UNTIL THIS MORNING, when I sat down to write this post. In other words, I’ve gone nearly 28 years at least partially believing woodshedding means to literally or metaphorically SHED SOME WOOD. Welcome to the Known Unknowns.

Why would this matter? What’s the difference between honing a craft and, well, honing a craft? It’s in the intent. You can whittle or sculpt anywhere, in front of anyone — in a group, even. In the (actual) intent of woodshedding, it’s about removing yourself from others and Getting Down To It, no matter how ugly It may be.

When I start working with a new workshop, I usually ask everyone some basic questions:

- How often do you write?

- What time of day do you write, and for how long?

- What do you do with your first drafts after you’ve finished?

- What’s your revision process? (Do you go back in and revise, or do you fully rewrite?)

- Do you read your work aloud to yourself?

- To whom do you show your work?

I’ve talked about some of these things here — especially the rewriting/revision process. When you write and for how long is a completely personal decision, unlike, say, baptizing someone’s dead relatives into your own religion. You know best when you work best. (Unless you’re frustrated and yet have never tried anything else, which I would gently encourage you to do.) But let’s talk about the importance of growing your work in captivity.

We all know Virginia Woolf’s revolutionary, transcendent essay “A Room of One’s Own.” And so we all know that I’m about to misuse it here, divorcing it from its crucial feminist allegory. Because as much as I’d like to, I can’t speak only to the ladies in the crowd. (Though I do holla at you, ladies, I do.) If you are writing, you need to work like a crazy comic-book villain, tucking yourself away and showing your work to NO ONE until such a time as it is ready. You need, frankly, a LAIR of one’s own.

This is tricky. Firstly because people may mistake you for a creep. (Unless you already were creep, in which case: Good job hiding in plain sight.) Secondly, because you may not have a fancy, private lair of your own available to you. You may have instead a basement that you share with other members of your family. You may have a table at Starbucks that that one fucking guy will not stop monopolizing with his three papers and his endless cup of coffee. You may have the front seat of your truck. Whichever the case, you need to make it a lair. Forbid anyone from entering that basement between 6 and 8AM on weekday mornings. Or write there late at night, when everyone’s too tired to bother you. Figure out when that fucking guy shows up at Starbucks and get there five minutes earlier, or go to the library. Park that truck somewhere remote and pleasant but not distracting. (Say, the parking lot of Home Depot.)

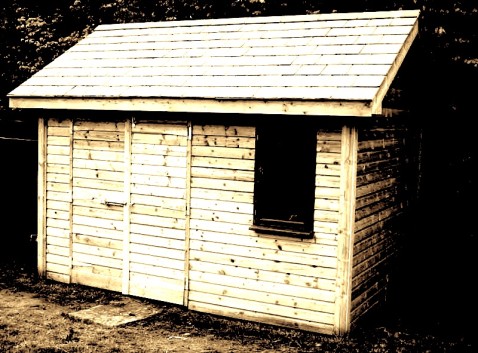

This is your woodshed. When you work there, commit to it. Do it at the same time every day, if you can. If not, try and get some semblance of a schedule — 8AM on Mondays and Wednesdays, 7PM on Tuesdays and Thursdays, some third example time on Fridays. Make yourself sit there for a specific block of time. If you have any sense of shame at all, you will become productive within this time period. Oh, and feel free to tell someone you’re doing this. That way they can say, “Hey, how was your writing hour today?” And then you will have to tell them an honest answer. Whatever it takes, buddy, whatever it takes. When you sit down to write, avoid distraction. Do not get up for coffee*, do not have laundry going that’s going to need to come out halfway through, do not fuck around on the internet, do not start a blog.

I now officially like “lair” better than “woodshed,” to the point where I wish there was a term called Lairing, but I guess they’re really the same thing. The point is to have a safe place to do your very best, and very worst, work. In fact, don’t worry yet if it’s either thing. Are you a writer or are you a critic? Just do the work. To quote Virginia Woolf yet again, Kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out.

When you have something, anything of a complete-seeming nature — a chapter, a story, a scene — then go back to your woodshed/lair and read the fucking thing aloud to yourself. I can’t stress enough the need to do this. In fact, get used to doing it for everything you write — work memos, emails, ransom notes. Flaws in language, logic, and character have a way of shining out here in a way they simply don’t when you’re reading silently. (Part of this is the way we read, which is to clump words and phrases together in our brains, grasping the collective meaning but often missing the individual parts.)

But you can’t work in a woodshed for all time. And you certainly can’t invite the whole world to come to your woodshed and read your work over your shoulder, though I suspect I’ve just invented a new installation piece for MoMA. Enjoy your grant, performance person! No, at some point you have to show your work to someone else. We’ve talked about this. You can do it.

BUT — and this is so important — DO NOT SHOW YOUR EARLY WORK TO SOMEONE WHO HAS A STAKE IN YOUR PERSONAL HAPPINESS. This is a phrase I did not invent, though I wish I had. More than that, I wish I could remember who said it, because it’s brilliant. It means a lot of things, this one phrase. First you have the spouse or family member or friend who just wants to see you happy and self-confident, and thus will not tell you what you wrote is a giant clump of shit. Then you have the person who secretly resents you and your writing and wishes to extinguish it immediately with their withering criticism. Then you have your own suspicions or resentments to deal with when the person reading your work has a stake in your life. Either you won’t take criticism (even if it’s spot-on) because you think they resent you, or you don’t believe their praise because, come on, you have them locked in your back bedroom. Of course they’ll say it’s good! They just want extra bread!

All of this means you have to find someone else to read your work. The easiest thing is to join a writers’ workshop or writers’ group. You do not have to spend money to do this, and you will get the added bonus of finding a like-minded group of people who are also just trying to make their work better. If you can’t find a group, put a notice up at your library. WANTED: SOMEONE TO EXCHANGE FICTION WITH. Doesn’t have to be complicated. And you can meet these people and assess them first to see if you have any sort of rapport. You don’t have to like the same kind of fiction, but you should try and find someone with a sensibility you trust.

I don’t, by the way, mean you should never show your work to your spouse or family or nasty friends. Just not your early stuff. Look: I revere my wife. She’s a legitimate goddamn genius (literally: Mensa-level) and a phenomenally smart reader and writer with an incredible bullshit detector. Through my own psychosis, if she were to look at an early draft and merely let me know she thought it wasn’t working, I would see the thing as irreparably damaged. It would be hard for me to get past. Let me stress that this is my own issue, because my wife has an amazing ability to make even the sharpest criticism sound like a helpful comment. (Which, duh, it is.) But let me also stress that having an awareness of your own issues is half the battle.

What I do is send my “early” stuff (meaning: I’ve written four or five real drafts and I feel it’s getting somewhere but I’m still not seeing all the problems I know are there) to my friend Eric Raymond. Eric is a seriously great fiction writer (and you will be reading his work very soon) and an invaluable reader. He’s sharp, he’s thoughtful, and he makes the kinds of suggestions that have literally transformed some of my crippled drafts into the stories they ultimately became. More than that, he will just tell me what’s not working, and it doesn’t hurt me to hear it. And I do the same for him. We’ve worked this way for going on ten years now, and I think we’ve had some good results. We’re not the only readers of each other’s unfinished work, but I do consider Eric to be one of my two most valuable.

The other? My wife. I know what I just said, but something magical happens because of the way I’ve learned to work: After I’ve brutalized my stuff and after Eric has weighed in, and after I’ve either incorporated his suggestions or been inspired to take the damn thing on a new 90-degree detour (one of the unsung benefits of having a trusted reader), then I show what I think is the final draft to Caissie. Except I know it’s not really the final draft. You see, Caissie is my Ultimate Reader. Every writer should have one, and every writer should be lucky enough to live with theirs. If she likes it, I know I’ve got something good on my hands. And even if she likes it, she’s such a sharp reader and unique thinker that she’ll find the emotional disconnect or weird character moment that, when addressed, can make the thing, finally, whole. This is the final batch of splinters and shavings on the ground by my feet. (Unless I have a sudden, terrible/amazing realization after the thing’s already out for consideration somewhere. Which has happened, but I’ll talk about that some other time.)

But none of that would work if I didn’t first hide myself away in the lair. Woodshed! Lair. Mine happens to be mobile — right now I’m working at the desk in our office, other times it might be the living room while the dogs are napping; I do still haunt the local Starbucks occasionally, because although the drink they serve is literally ruined coffee, the table-to-chair height ratio just can’t be beat. As a writer, it’s not a privilege to have a place — any place — where you can go fail and struggle and triumph in peace, away from the questions and concerns of even the most well-meaning people in your life. It’s necessity.

What an excellent article! As a pianist/piano tutor I wondered what Mike Cornick’s little jazz piano composition,” ‘Woodsheddin’ ” was all about. Now I know. As a musician I also know how important it is not to show other people one’s work in the early stages of creation. Reveal nothing until you have something you are pleased with, something substantially finished.

Thanks for a great read!

Cheers, Malcolm

I am just amazed that no-one else has seen fit to comment on this piece in almost two years since I wrote the above. Amazing . . .

PS Matt’s contribution, not mine!